“Trees in Winter” was a “before” quiz, an assessment of what you already know or can aim to learn. It limited the selection of trees to those living at the Ames Free Library, a manageable group growing on a small, easily-traversed property. I hope that their names and images will stay in your mind as you visit the library. The game will remain open as a learning tool even after the contest closes on February 10.

From the responses thus far, it is clear that the most challenging task for participants is twig and bud identification. Although you may be accustomed to viewing trees in their entirety, paying attention to the details of twigs will give you the tools to distinguish species with some confidence – and they are far less variable than bark. So, here are some guidelines to get you started.

Twigs: Questions & Contrasts

To identify twigs, you must assess their qualities. These are readily observable while holding one in your hand, but a good lens will help reveal fine details. Ask yourself a series of questions as you examine the specimen.

Is it stout or slender?

Stout (black walnut)

Slender (American elm)

Did your twig grow straight or zigzag?

Straight (scarlet oak)

Zigzag (black locust)

Straight (scarlet oak)

Zigzag (black locust)

Does it have hair or thorns?

Hair (staghorn sumac, a large shrub or small tree)

Honey Locust Tree Thorns in Kansas

John P Salvatore, CC BY-SA 4.0

If you scratch or break the twig, does it have an odor?

Wintergreen (black birch)

Bitter Almond (black cherry)

Is there anything distinctive about the twig’s color?

Green Twig (sassafras)

Yellow Twig (willow)

Is there anything attached to the twig? Some remnant of fruit, for example? Paying attention to last season’s pods, catkins and fruit can narrow the options down to a few plant families.

Fruit (crabapple)

Cone-like Fruits (tulip tree)

Catkins (birch)

Cone-like Fruits (tulip tree)

Catkins (birch)

By sharing these photos and questions, I am demonstrating a process of learning. The development of observation skills is an activity, one that requires not only looking but also thinking and wondering. We tend to see what we expect to see - and develop conclusions based on what we already know. Asking new questions allows us to see more.

Buds: Recognizing Major Features

Next, let’s consider buds. The buds that you see in winter formed during the preceding growing season. They contain the tree’s future leaves, flowers, and branches and will grow when conditions are favorable in spring.

Are the buds of your specimen in an opposite or alternate arrangement along the twig?

Opposite (red maple)

Alternate (linden)

The answer to this single question will split Massachusetts deciduous trees into two groups. The smaller group, the opposites, includes a limited number of plant families which can be remembered through the mnemonic, “MAD Horse.”

Maple

Ash

Dogwood

Horse chestnut

The best known native dogwood, the beautiful flowering dogwood, has onion-shaped flower buds.

Cornus florida, in Arboretum de la Vallée-aux-Loups

Dogwood Flower BudsHorse chestnut, a European native, is the only tree in its genus commonly planted in our area. It has enormous, sticky buds.

Horse Chestnut Bud

Peter O'Connor aka anemoneprojectors from Stevenage, United Kingdom, CC BY-SA 2.0

That leaves maples and ashes. We’ll get back to them, but first let’s focus on some ways to distinguish buds.

Some trees produce twigs with a single terminal bud, that is, one bud at the end of the branch.

Single Terminal Bud (linden)

The terminal bud can be much larger than the lateral (side) buds. Look at the flower buds of this magnolia!

Large Terminal Buds (Magnolia)

Other twigs, like this oak branch, end in clusters of buds.

Cluster of Terminal Buds (oak)

It is useful to evaluate the size, shape, texture, and color of the buds.

The conspicuous flower buds of silver maple are visible from ground level, while the ginkgo’s buds are barely noticeable.

Silver Maple

Ginkgo

The ginkgo has stubby buds; compare them with the elongated buds of beech.

Differences in shape and texture may be found within the same genus; indeed, these details help distinguish one species from another. Here are two sets of oak branches. Buds on the first plant are pointed and very woolly. The second specimen has smooth, rounded buds.

Woolly & Pointed (black oak)

Smooth & Rounded (white oak)

Woolly & Pointed (black oak)

Smooth & Rounded (white oak)

As mentioned earlier, some tree buds have a distinctive shape. The two species shown below stand out from the crowd.

“Duckbill” (tulip tree)

“Cone” (sycamore)

Examining buds is a good way to savor the diversity of trees in Massachusetts as well as a step towards identifying them. I would like to tell you that, with a few easy guidelines, you’ll be able to ID all those trees in your community. In truth, there is seldom a one-to-one correspondence between a feature and a species: “Pointy buds? It must be tree x.” Yet each species has a cluster of characteristics that, together, define its identity. Learning how to describe a twig and its buds will give you the tools to consult a field guide or key - or to ask a more experienced naturalist. It’s also fun. Really.

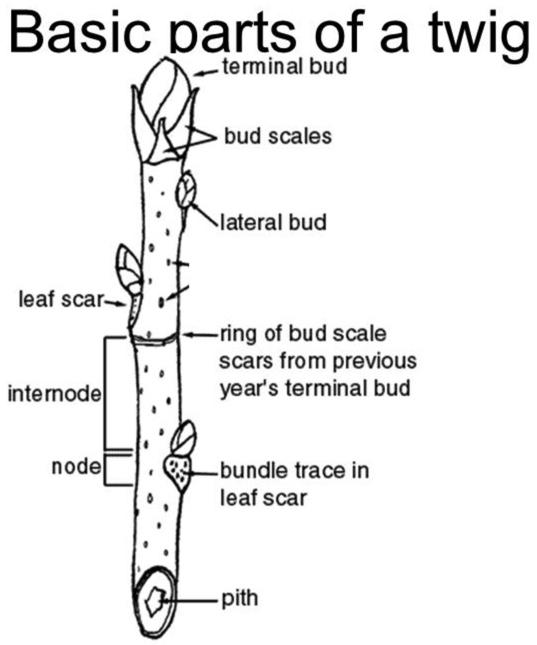

The Finer Details: The Twig Tells a Story

Clearly, a twig with buds is much more than a stick with bumps. The twigs of woody plants develop their forms as a result of their growth patterns: each feature reflects part of the growth process. As we review a bit of twig anatomy, please refer to the diagram below.

Via Pinterest, Originally from Clemson University?

During the winter, dormant buds are protected by scales. Like shingles on a roof, scales shield the oak buds pictured below.

Not surprisingly, the shape and number of scales can vary. Willows are distinguished by having only one hood-like scale covering each bud.

Single Scale (willow)

As spring progresses, the expanding leaves outgrow their protective covering. This image of American beech includes a closed bud (upper center), a leaf just starting to unfurl, and several leaf clusters that have almost shed their scales.

This photo also displays whitish “growth rings” in the upper right corner. These are actually scars left when last year’s terminal bud scales fell off. The twig grew the distance from scars to the tip in one year.

When the leaves eventually fall off, they leave scars on the branch, scars with a consistent pattern. That brings us to last week’s image:

Leaf Scar, Bud, & Lenticels (tree of heaven)

The pale, heart-shaped area marks the spot where a leaf was once attached. The protuberance nestled in the top of the leaf scar is one of the tree’s buds, protected by scales. All those speckles on the bark are pores that allow air to move between the atmosphere and the tree’s internal tissues. They are called lenticels, and on some species, such as birches, they are very noticeable. If you want to see this young tree in person, visit the retention basin closest to the walled garden at Queset House.

On an even smaller scale, the leaf scars contain bundle scars, remnants of the plant’s vascular system. Small dots indicate where veins transported food and water between the leaf and the stem. I’ve magnified the bundle scars in this image of a red maple twig.

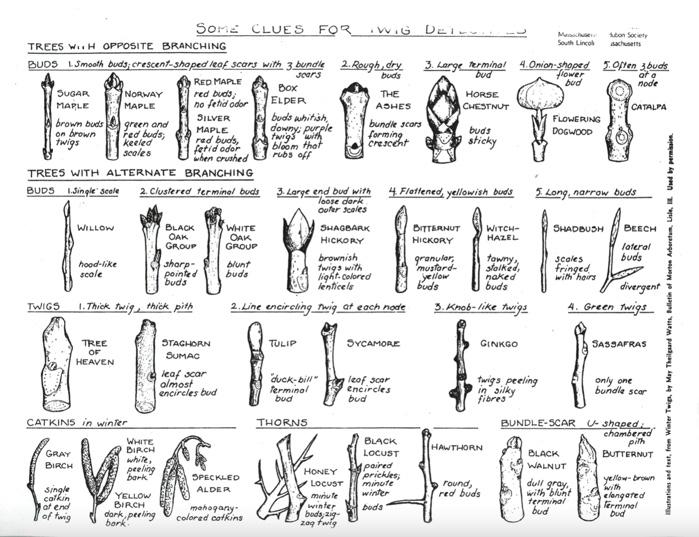

As insignificant as all this may seem, these features contribute to the tree’s identity. A tried and true guide to twig anatomy is the 2-page fact sheet entitled “How to be a Twig Detective” adapted by Mass Audubon from a Morton Arboretum Bulletin illustrated by May T. Watts. It’s an eye opener. Click on the image below to link to a vintage scan.

Courtesy of exordium-adventure.com

To conclude, let’s return to the maples and ashes. You will recall that these two genera have opposite leaves and leaf buds (MAD Horse). With your new knowledge of twig anatomy, it will be easy to tell them apart.

Ash is described as having “stout twigs” and “rusty brown” buds. The terminal buds are “rough and dry,” and the leaf scar is “notched at the top” and “somewhat horseshoe shaped.”

Ash

Botanical keys describe red maple as having “slender” “dark red” twigs and “reddish” “clustered buds.” The leaf scars “are narrow” with “3 bundle scars.”

Maple

Room to Explore

To help develop this interest with the least frustration, I’d recommend books and websites that are specific to trees in winter.

A nontechnical winter key to the fifty trees, which was originally published by Cornell University, emphasizes “brevity and simplicity” as it helps identify trees of the Northeast.

The University of Wisconsin’s Winter Tree Identification Key has a similar style.

The Winter Tree Finder: A Manual for Identifying Deciduous Trees in Winter is a pocket guide specific to Eastern North America.

The Identification of Trees and Shrubs in Winter Using Buds and Twigs published by Kew has gorgeous illustrations, but its worldwide distribution and inclusion of shrubs might make it daunting for a beginner.

The Sibley Guide to Trees is more widely available and has fine illustrations, but twigs and buds are not its main focus.

And then there’s first-hand experience:

–Collect several twigs this week

–Look at them closely when you get home

–Describe three features of each one. Go ahead. Put it in writing!

At the Library

Identification of Trees and Shrubs in Winter Using Buds and Twigs

by Bernd Schulz

Available through Commonwealth Catalog

A Manual for Identifying Deciduous Trees in Winter

by May T. Watts