Houseguests are commonplace during the holiday season – at least they were prior to the coronavirus. While most guests receive invitations, a few unexpected visitors may take up residence in your space. Here’s one who usually arrives in autumn with the intention of spending the winter.

This brown marmorated stink bug recently moved into the third floor of the library. It posed for a portrait on one of the library’s oak tables in mid December.

This insect has a shield-shaped body with brown and cream mottling. Merriam-Webster defines “marmorated” as “veined or streaked like marble.” Its antennae have white bands, and its eyes are noticeably red. It can fly. Like other stink bugs, it protects itself by releasing chemicals that have an unpleasant odor. Here’s another look in better light.

A native of East Asia, the BMSB [brown marmorated stink bug] is a relative newcomer in our neck of the woods, one that presumably arrived via international shipping. First reported in Pennsylvania in 1998, it has since spread across the U.S. and into Canada. According to the Massachusetts Introduced Pests Research Project, it appeared in Bridgewater in March, 2007. Several years ago, this species commanded my attention when many individuals moved into my house. The clicking sounds of their landing on walls and lamps formed a new soundscape, and they had the annoying habit of landing on me or my work. That’s when catch and release (back into the cold outdoors) became a daily routine. I wondered why “all of a sudden” this had become a problem, but, apparently, their populations had been growing and expanding since I moved into my current home.

Authorities, including the EPA, emphasize that this species does not bite, transmit disease, or cause damage to the home. Nor will they have babies while visiting. They are merely seeking shelter from the cold, hoping to settle down into hibernation until they depart in spring.

Unfortunately, the BMSB is not harmless in the outdoor environment. It is a sucking insect that is causing serious damage to fruits, vegetables, and ornamental plants, especially in the mid-Atlantic where it is now well established. Like other invasives, it has few impediments to its expansion, though agricultural researchers are assessing the potential of a non-native parasitoid wasp that targets this stink bug’s eggs. Regrettably I can, once again, claim some first-hand experience: over the last few years, my young apple trees have been producing deformed fruit. I chalked this up to general neglect until I read about “cat facing,” a fruit deformity caused by some insects including the BMSB. The image below shows this particular type of damage.

BMSB Damage to Apples

Credit: Penn State Extension

This year, fewer BMSBs have joined my household, though one landed on my laptop as I was researching this post on Wednesday. If you haven’t been as lucky, try using a vacuum cleaner to scoop them up. The best approach is prevention. UMass Extension, and every other site that I encountered, recommends sealing all crevices where the insects might gain entry: around doors, windows, screens, vents, pipes, chimneys and the house foundation.

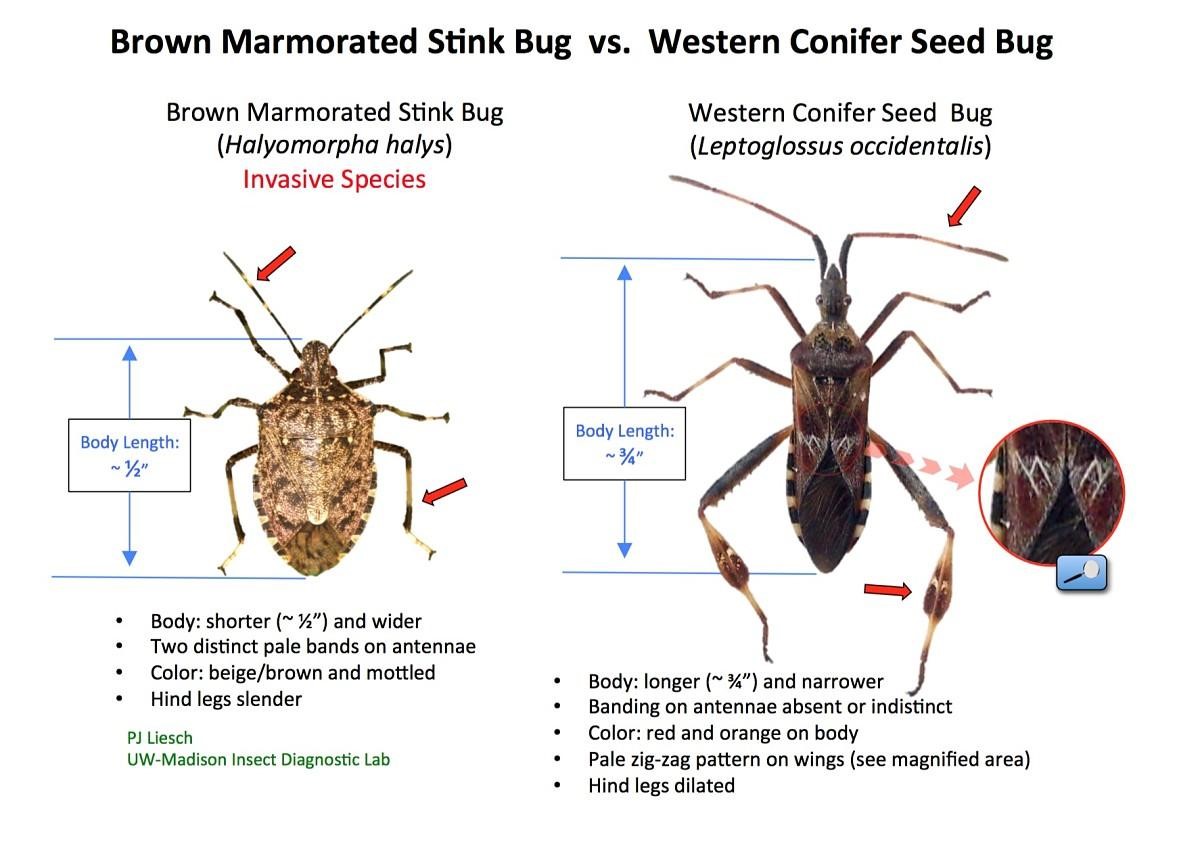

Several other insects have become what UMass Extension calls “House Invaders.” One is the western conifer seed bug which is similar to, but more slender than, the BMSB.

Credit: PJ Liesch, UW-Entomology

Another insect that might arrive en masse is the Asian ladybird beetle. It prefers my dining area.

Not all seasonal visitors have six legs.

Each year, at least one eastern meadow vole finds its way through the gaps in the fieldstone foundation of my old house. At the end of this past September, staff found one of these cute rodents, also known as field mice, scurrying about the library. Eventually, staff and patrons were able to guide it towards the open door.

Meadow Vole

Courtesy Owen Strickland/iNaturalist CC BY-NC via chesapeakebay.net

Chimney swifts, bats, flying squirrels, and mice might also set up shop. Years ago, before the Ames Free Library’s renovation, I met a toad in the staff rest room on the ground floor.

Though we may be reluctant to acknowledge it, we humans share our homes with a host of other species, many of whom are year-round residents. For a playful, but informative, overview of this topic, watch “The Great Wild Indoors,” a 48-minute documentary from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation which is available through the free streaming service called TubiTV. The program follows a team of entomologists who visit a typical Toronto home in order to conduct a census of arthropods, the phylum that includes invertebrates such as insects, arachnids, and crustaceans. As a CBC article explains “. . . our homes are indoor biomes, where insects have learned to thrive. And amazingly, each room in a house can be thought of as its own ecosystem.”

The entomologists from “The Great Wild Indoors” previously studied the indoor biome of 50 houses in the Raleigh, North Carolina area. The results of their 2016 report are fascinating. Insects and spiders lived in 100% of the houses. Among the most common were ants, book lice, carpet beetles, and fungus gnats – those small flies that live in potting soil. The data was categorized by room function. Not surprisingly, camel and cave crickets were most common in basements, while ants concentrated on kitchens. An average of 93.14 arthropod species (not individuals!) inhabited these homes, but the authors considered this a conservative estimate. Most of these species keep a low profile, going unnoticed by their human neighbors. Some are quite small; others are nocturnal. “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” offers illustrated profiles of eight of them.

These animals have adapted to life in the dry, unnatural conditions of our homes and, apparently, they have been doing so since humans lived in caves. It is likely that they migrated with us across the globe. Given that humans spend nearly 90% of their time indoors, it’s surprising how little we know about our closest neighbors. Perhaps we fear knowledge that would make us uncomfortable. Michelle Trautwein, a research scientist on the indoor bug census team, holds a different view: “A diversity of benign roommates is not going to be harmful . . . This is just part of life on Earth.”

At the Library

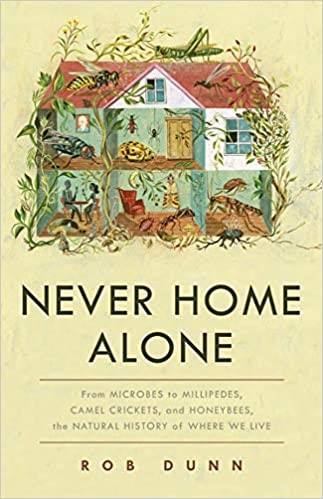

Never Home Alone : From Microbes to Millipedes,Camel Crickets, and Honeybees,The Natural History of Where We Live

by Rob Dunn

The Living American House: The 350 Year Storyof a Home–an Ecological History

by George Ordish

by Nancy Honovich

Available through the Commonwealth Catalog