See what’s happening on the grounds of the Ames Free Library or nearby areas with “A Glimpse of Nature.” Offered by Lorraine Rubinacci, the library's resident naturalist, this weekly photo blog is a gentle reminder to enjoy the wonders that surround us.

A Glimpse of Nature - "Cottontail"

A library patron recently forwarded some photos of life in Queset Garden. Here’s one of the creatures that he spotted near the garden’s trelliswork:

Image courtesy of Brian Woodward

Brian’s cottontail image demonstrates several typical characteristics of this animal. First, it is shy and wary, ready to disappear into the safety of the shrubbery. Its brown and gray fur is camouflaged, making it somewhat difficult to distinguish from the bark mulch. It is solitary. How many times have you seen a herd of rabbits? Notice also the angle of sunlight which indicates that it is either morning or late afternoon. Cottontails are most active between dusk and dawn. This, too, is a safety feature: rabbits who feed in low light might better avoid predatory eyes, especially those of raptors.

We’ve all seen this animal which is common around human habitations, though many sightings reflect the animal’s anxiety at our presence. We see the rabbit “statue” freezing to avoid detection or the leaping rabbit bounding away.

The cottontail’s edginess is justified. It is preyed upon by cats and dogs, coyotes, foxes, bobcats, owls, hawks, weasels, snakes, people, and other hungry animals. Paul Rezendes, author of Tracking & The Art of Seeing, says that “the cottontail is North America’s primary prey species.” They survive less than two years in the wild. Indeed, according to an article on MassAudubon’s website, “Nearly half the young die within a month of birth.” This would, of course, include causes other than predation, but the statistic demands some perspective. For many years, I’ve been pleased to see “the” rabbit in my backyard, naively referring to my sightings as if there were one ancient individual living there. How many generations of rabbit have I briefly witnessed?

This is a harsh reality for the rabbits and difficult for people who empathize with this gentle creature. Like another cute herbivore, the meadow vole, the cottontail is an important part of the food chain. It’s presence supports the diversity of New England wildlife.

Many features of the cottontail’s anatomy and behavior help thwart its predators. Let’s take a closer look at this Queset Garden rabbit sitting near the jewelweed.

Powerful hind legs enable speeds up to 18 miles per hour and 10-foot leaps. The prominent ears can rotate to gather sound more efficiently. Large eyes on the sides of its head provide great peripheral vision. It’s blessed with a good sense of smell as well. Speed, camouflage, sharp senses, and protective habitat all help the species survive.

So does its reproductive strategy: cottontails are so prolific that they can survive heavy predation. Females bear several broods per year with multiple “kits” per brood. There is a short gestation period, and kits grow quickly from helpless, blind infants to active, independent juveniles. Despite numerous hazards, eastern cottontail rabbits thrive . . . but there is another Massachusetts rabbit, the New England cottontail, that is in serious trouble.

The New England cottontail is our native species; eastern cottontails were introduced by hunting clubs in the early 20th century. As the eastern rabbit expanded its range, populations of the New England species have plummeted. In 2006, a U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service fact sheet considered the possibility of protecting the New England cottontail through the Endangered Species Act. Fortunately, a coalition of conservation groups, government agencies and private landowners have developed and begun to implement an action plan to increase populations of the beleaguered creature.

One difficulty in protecting the New England cottontail is that it is very difficult to distinguish between the two species by external appearance: the differences are slight, and variations are common. These days, researchers can pinpoint the species by analyzing the DNA of fecal pellets.

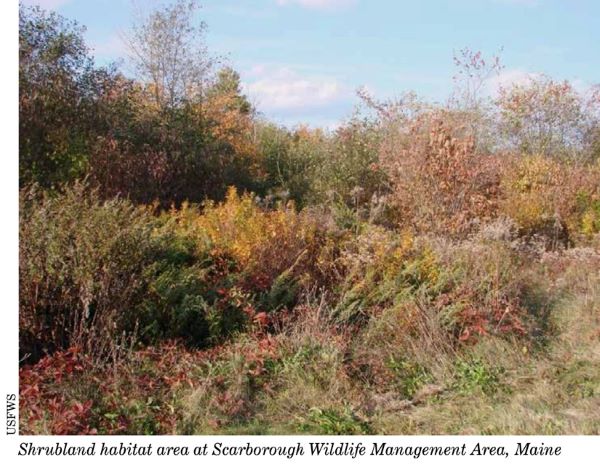

A significant difference between the two similar rabbits is their habitat preference: eastern cottontails, who have slightly larger eyes, spend more time in the open; New England cottontails prefer dense thickets. Thickets, also called “young forest” or “early successional forest,” were very common as New England’s agricultural lands were abandoned. Now many of those former fields have been developed or have grown into mature forest. The New England cottontail cannot thrive in either of those situations. The species’ recovery plan focuses on protecting or creating new young forest habitat. It turns out that shrubs and young trees provide food and shelter for many species including box turtles, woodcock, ruffed grouse, and prairie warblers. Creating habitat for the New England cottontail will benefit an entire community of plants and animals.

A centerpiece of this project is the new Great Thicket National Wildlife Refuge. Excited to visit this new refuge, I quickly learned that it is a long-range project that will protect suitable parcels of habitat in New York and New England. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service is authorized to purchase up to 15,000 acres from willing sellers. This will take time. As parcels are acquired, a breeding program is also underway. “A Secluded Island And 13 Rabbits: Inside The Plan To Revive The New England Cottontail” describes the effort to establish a population on Nomans Land Island, in hopes of transferring young rabbits back to protected areas on the mainland.

To learn more about this animal’s life history, behavior, habitat needs, and restoration, visit New England Cottontail.org. I know that I’ll be watching cottontails more carefully, especially in my local thickets. To get you started, observe this rabbit feeding near the Queset Garden stage. Notice the way its left ear turns towards the end of the clip.

At the Library

Tracking and the Art of Seeing: How to Read Animal Tracks & Sign

by Paul Rezendes

Behavior of North American Mammals*

by Mark Elbroch *This item can be accessed through the Commonwealth Catalogby Christina Leighton