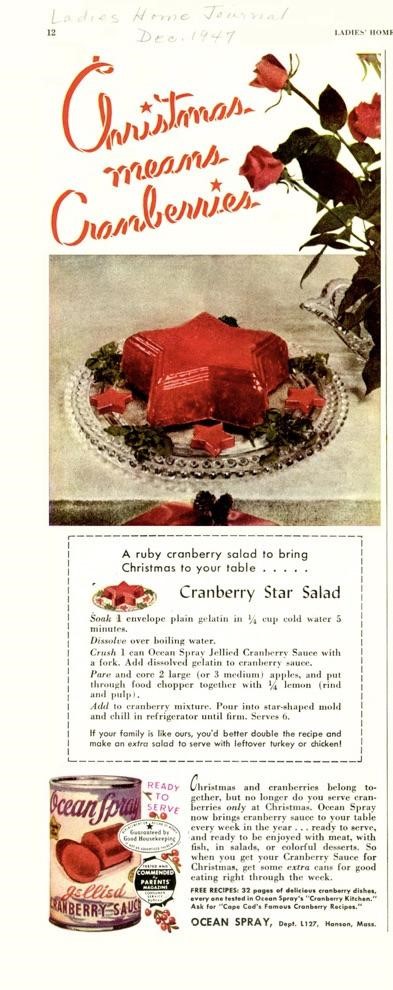

“Christmas Means Cranberries” . . . at least that’s what an Ocean Spray advertisement in Ladies Home Journal proclaimed in 1947.

“Christmas Means Cranberries,” SAILS Digital History Collections

Like many Americans, I enjoy eating cranberries year round, but, I’ll admit, that the fruit and their bogs add a festive touch to New England life. So let’s consider cranberries this week.

While there are no bogs at the Ames Free Library, cranberries have been cultivated in Easton for some time. In his 1886 History of the Town of Easton, William Chaffin lists multiple bog operations, owners, and locations, including one along Whitman Brook, not far from the present Town Hall.

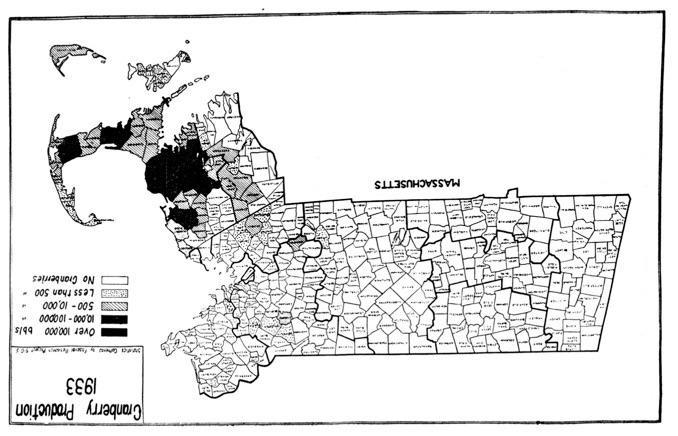

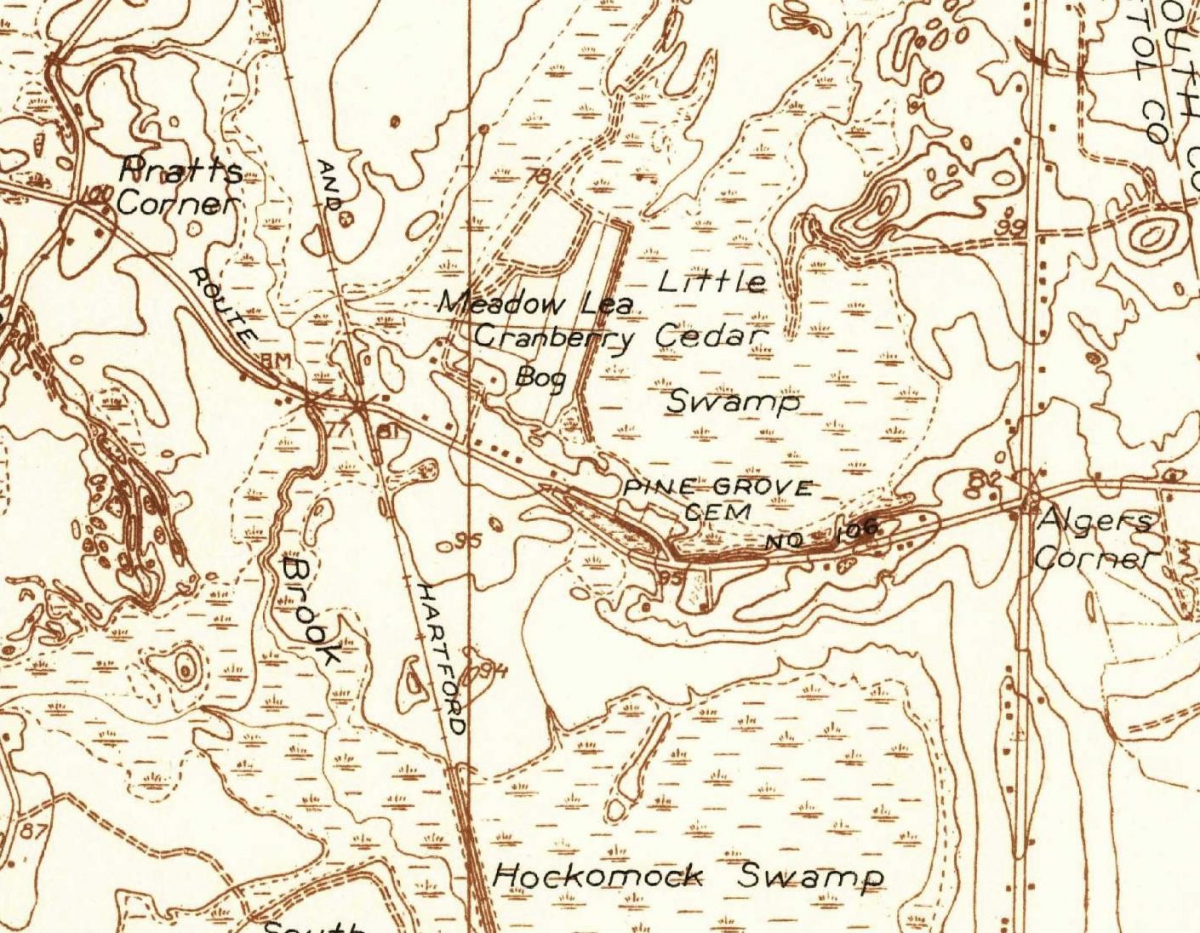

If the center of production has been further south and east -- in towns such as Carver, Wareham, and Middleboro -- Easton has been a secondary area for the crop, as you can see from the 1935 map below.

“The Cape Cod Cranberry Industry” by the Cape Cod Cranberry Growers’ Association circa 1935.

Accessed from SAILS Digital History Collections

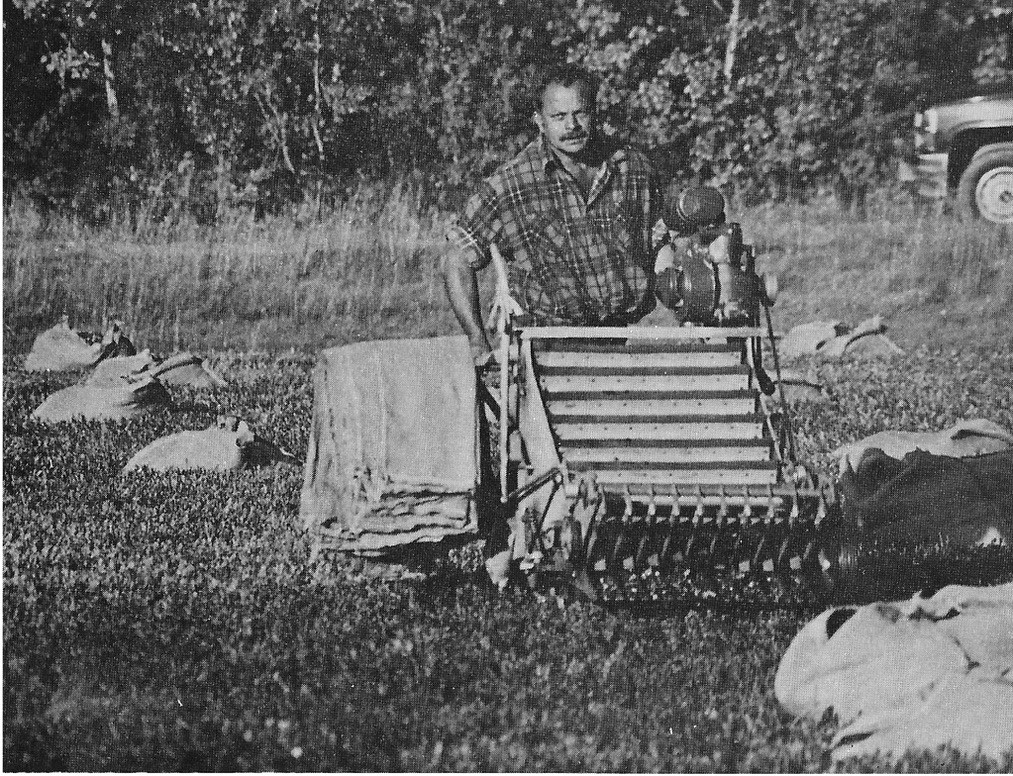

As of 1995, when Easton’s Neighborhoods was published, Meadow Lea bog off Foundry Street was producing 600,000 to 800,000 pounds of cranberries annually, much of it dry-harvested for sale as fresh fruit.

Dry Harvesting Cranberries

Easton Historical Society’s Flickr Page

Two cranberry farms still operate in town, though they would not be immediately apparent to the casual observer. Meadow Lea, mentioned above, was recently sold by Morse Brothers to a new owner. It is north of Southeastern Regional Vocational Technical H.S. The other bog, Fairland Farms, is primarily situated in Norton, with a small amount of acreage along Bay Road in Easton.

As a native American fruit, the cranberry had been wild-collected centuries before Captain Henry Hall of Dennis began experimenting with cultivation in 1812. The species thrives in our coastal landscape, a land created by receding glaciers which left sand and soggy depressions behind. It needs acidic soil, adequate water, and cold winters. A review of its natural history will help explain both its wild origins and the agricultural techniques that transformed the fruit into a major crop. The topic of this post, afterall, is “Bogs” – not “Cranberries” – and its focus is the relationship between the natural landscape and human activity.

The cranberry plant is a perennial trailing vine whose horizontal stems, called runners, form a dense mat.

Burrage Pond WMA, Hanson, October 14, 2020

Flowers and fruit develop on vertical stems called uprights. Growers periodically apply sand to their bogs in order to encourage this upright growth and to increase fruit production. The flowers, reminiscent of a fanciful crane’s head, give the fruit its name.

Crane-berry

In earlier times, farmers in southeastern Massachusetts modified wetland areas that already met some of their crop’s needs. The right conditions were often found in peatlands, wetlands that are acidic and low in oxygen and nutrients, places where partially dead plant material accumulates into thick layers because it decays slowly. The primary plant in many peatlands is sphagnum moss.

Several types of bogs occur naturally in our area. Some of them, like Black Pond Bog shown below, possess a thick floating mat of sphagnum moss that, in turn, supports other vegetation. The pond itself is a kettlehole, a depression left behind by the retreating glacier.

Specially adapted plants such as cranberry, sundew, and pitcher plants grow on the mat. Shrubs and Atlantic white cedar trees form the outer rings.

Spatulate-leaved Sundew, Burrage Pond WMA

Pitcher Plants, Black Pond Bog Preserve, Norwell

Closer to Easton, one can visit the Ponkapoag bog boardwalk in Blue Hills Reservation.

Cranberry farms were also constructed in Atlantic white cedar swamps after their valuable, rot-resistant timber was lumbered. If you are not familiar with this impressive tree, I would encourage you to visit the Hockomock Swamp’s sizable cedar forest near the Easton/Raynham border. These same wetlands were sometimes mined for bog iron, especially in Plymouth County.

This leads us back to the Meadow Lea Bog which was created by building a dike at Little Cedar Swamp back in 1910. Even in 1936, the neighborhood was predominantly wetlands with few houses. The section of map below reminds me of Chaffin’s observation that “The swampy lands and numerous small watercourses of Easton offer favorable opportunities for this important business.”

USGS topoView

Here’s the eastern end of Little Cedar Swamp on April 3. Most of the bog is open, dominated by herbaceous plants (leatherleaf, I presume). At the edge are young Atlantic white cedars. Beyond them, red maples and some white pines grow. Presumably, there were many more cedars before the area was lumbered.

Little Cedar Swamp Behind Pine Grove Cemetery

To convert bogs and cedar swamps into farmland, the existing vegetation was removed, the ground leveled, dams and channels installed to control water flow, and sand applied to the bog’s surface. Prepping the land for planting could be backbreaking work.

Once established, the bog needs to be managed throughout the seasons. In early spring when our trees are first leafing out, the vines have a soft fresh look.

Near Round Pond, Duxbury, May 21, 2020

By late June/early July, when they are covered with small flowers, bog owners will bring in bees to pollinate them. During the growing season, the bogs aren’t submerged.

In autumn, both the plant and its fruit turn red: the fruit is ready to pick. Berries that will be used to produce juice are harvested using the wet method, that is, by flooding the bog so that the buoyant fruit may be easily gathered. Cranberry plants are adapted to seasonal flooding. Indeed, wild cranberries disperse their seeds by water. Flooding is also used to protect the plants in winter. Managing the crop requires careful attention to weather conditions.

To learn more about the natural history of cranberries, visit the UMass Cranberry Station’s website. An introduction to cranberry farming techniques can be found at the “How Cranberries Grow.”

Austere Beauty: The Cranberry Bog in December

During two hundred years of cultivation (and considerable marketing), the uses for cranberries have multiplied. In addition to fresh and frozen fruit, new markets have developed for juice, juice blends, and sweetened dried fruit. Cranberries are also being used in a variety of health and beauty products In response to this increased demand, the fruit is now sold and grown internationally.

The world of cranberries keeps changing. In recent years, the center of production has shifted to Wisconsin, where 60% of the world’s crop is grown. Massachusetts growers are faced with new competition from farms in Canada and South America, new pests, new hybrids, and new impacts from climate change. Remember that the cranberry, as a species, needs cold winters in order to be productive – and winters are growing milder in New England.

One consequence of the cranberry industry’s struggles is that some farms are being converted to other purposes such as housing and conservation land. Southeastern Massachusetts now offers many bog preserves including the Cranberry Watershed Preserve in Kingston, Tubb’s Meadow Conservation Area in Pembroke, and Burrage Pond Wildlife Management Area in Hanson and Halifax, to name just a few.

While some of these properties are actively managed for wildlife value, most become reforested, as pioneer plants take hold in the full-sun conditions. The first photo below shows a bog in the early stages of reversion: grasses are just beginning to displace the vines. The second image depicts a bog that was abandoned many years ago.

In some cases, the land’s ecology is coming full circle. Unusual and spectacular changes can be observed at the Tidmarsh Wildlife Sanctuary in Plymouth, where Mass Audubon chose to fully restore the property’s natural communities and waterways. This impressive project is “the largest freshwater ecological restoration ever completed in the Northeast.” Plan a visit.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Perhaps this week you’ll serve cranberry sauce at dinner, or assemble a popcorn and cranberry garland, or walk the perimeter of a former cranberry bog. As you do, take a moment to consider the ever-evolving Massachusetts landscape and the role a small berry has played.

At the Library

by Charles W. Johnson

America’s Founding Fruit: The Cranberry in a New Environment

by Susan Playfair