See what’s happening on the grounds of the Ames Free Library or nearby areas with “A Glimpse of Nature.” Offered by Lorraine Rubinacci, the library's resident naturalist, this weekly photo blog is a gentle reminder to enjoy the wonders that surround us.

A Glimpse of Nature - "Great Blue Heron"

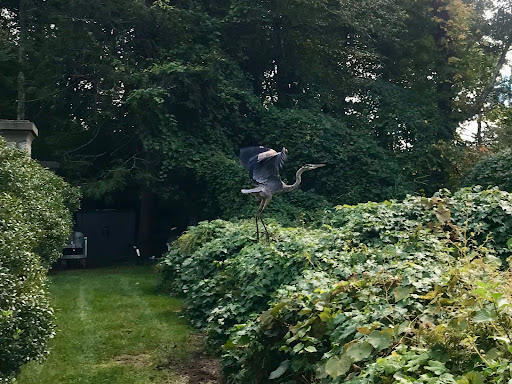

To observe wildlife, it helps to know the animal’s life history and habitat preferences. White-tailed deer frequent forest edges, porcupines relish hemlock forests, shorebirds congregate at . . . . All the same, we’re sometimes caught off guard. I recall one wilderness trip in northern New England that offered few mammals until a beaver appeared behind my roadside motel. Recently, my coworker, Lily, was treated to this sight on her way to the staff parking area.

Credit: Lily Goldstein

Great blue herons are not rare in Massachusetts, and to find one hanging out near the library’s intermittent stream is natural enough. All the same, one doesn’t expect to bump into a four-foot bird near a busy driveway.

Let’s spend a little time with Lily’s photos for they illustrate several features of this species.

First, we should note that the bird is solitary, which is typical of great blue herons when they are not breeding.

This individual is located near suitable habitat. There’s the intermittent stream, of course, and the small pond opposite the driveway. Queset Brook and its associated ponds -- Shovelshop, Langwater, and Ames Long Pond -- are nearby. These herons feed at both freshwater and saltwater wetlands including pond edges, river bends, and marshes. They are easily observed from the water.

While the marshy edge depicted above might be typical, it is not uncommon to see great blue herons at artificial fish ponds. Indeed, this is where my colleagues most often see one.

Credit: Lily Goldstein

It comes for food. Those of you who visit the garden’s reflecting pool know that it supports some fish, both intended and “accidental.” In spring, American toad tadpoles abound, followed by toadlets. Aquatic insects and a few dragonflies round out the menu. The species hunts a wide range of prey including fish, amphibians, insects, crustaceans, and sometimes small mammals. Feeding is an easy behavior to observe because it is a slow-motion affair: the bird stalks by standing still or walking slowly, then strikes prey with its dagger-like bill by either piercing or grasping it. HeronConservation calls the great blue heron “a specialist at patient feeding.” Its website comments that “Great Blue Herons devote considerable time to subdue and prepare prey for swallowing.” Think of all those fish bones!

Another thing to note about Lily’s photo is the time of day. It’s dusk, a time when some birds might not be feeding. This wouldn’t hinder a great blue, however, for this species has good night vision.

A few years back, one of the library’s volunteers lamented a great blue’s visits to her koi pond. Though there are tricks to frighten off the birds (such as using mylar) or to safeguard the fish (with sheltering underwater tubes), my best advice is to shift one’s attention and joy from the fish to the bird. Although this species is now common in Massachusetts, that was not always the case.

Populations of great blues plummeted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when feathered hats were fashionable. The slaughter of birds for this purpose led to the creation of Mass Audubon and the passage of laws protecting migratory birds. For decades, there were no breeding colonies in Massachusetts. Protection of the birds and the wetlands they utilize gradually reversed this decline. The species received an additional boost in the 1990s when a ballot initiative banned leg-hold traps, formerly used to trap beaver, another species driven to the brink.

Like the koi-eating heron, beavers are often maligned because they change the landscape without consulting us. Their construction of dams creates pond communities that benefit many species, not least of all, the great blue heron. These birds nest in tall, dead trees where they build large stick platforms for their young. When beavers dam woodland streams, the higher water level in the new ponds kills the submerged trees. As their leaves fall, the remaining trunks and limbs offer strong, open structures to support the displaying herons and their nests. Even better, the new colony is surrounded by water which deters some of the predators who might be attracted to heron eggs and chicks. As beaver populations have rebounded, heron colonies have as well.

The article “Great Blue Herons Make a Comeback” explains the role beavers are playing in the heron’s recovery. For an excellent summary of the bird’s population trends, see The Breeding Bird Atlas 2 species account of Great Blue Heron.

I was fortunate during 2020 to visit an active heron rookery, one that had been enabled by beaver activity. It was the end of April, the herons were already paired at their nests, but chicks were not yet visible. As you can see from the image above, the nests are high and protected by the water below. Herons prefer undisturbed breeding sites; I worry that this one might attract too many visitors.

For a great blue heron, parenting is a major commitment: finding a site, a mate, and constructing a nest is just the start. According to the All About Birds entry on “Great Blue Heron,” the parents need to sit on and protect their eggs for 28 days. The HeronConservation website quotes a study that claimed “Incubation is continuous after the first egg, consuming 54 minutes of each hour.” Then the hatchlings must be protected and fed . . . and fed. . . for another two months (49 - 81 days). The parents take turns on these relentless shifts.

Seeing these giant birds buffeted by winds in the treetops is very impressive. Here is a brief (48 second) clip from my Stepping Out video, “Nesting,” which conveys the experience of the birds and their observer.

Let’s get back to “Lily’s bird.” After being pursued for a few too many photos, the bird lets out a harsh croak and launches into flight. It rises with slow, powerful wingbeats, trailing its long legs behind. You can see the two-toned wings and the beginning of an “S” curve as the bird tucks its neck back.

Credit: Lily Goldstein

As it gains elevation, the familiar silhouette takes shape.

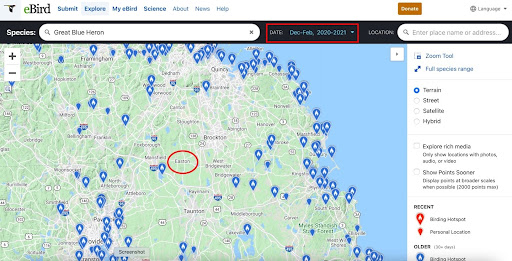

Will we see this bird again? Perhaps. The library photos were taken on October 7. Though some great blues overwinter in Massachusetts, most migrate in the fall and return in late March. Birders are still reporting sightings in southeastern Massachusetts this week. Yet records on eBird from the winter of 2020/2021 indicate that most sightings were along the coast where there’s open water. Sorry to say, but Queset Garden’s reflecting pool will freeze soon enough.

In the meantime, stay alert for the handful of winter residents and prepare for the return of this grand bird in early spring. If you frequent a particular wetland area, you might become acquainted with an individual heron as it visits, and defends, its feeding territory. Our Queset Garden bird might return for tadpole season.