Several readers identified “What Is It! #8” as an owl pellet. I expected this, but the discovery of a pellet gives me an excuse to delve into a fascinating topic.

Last April I found this particular pellet under a large pine between Queset House and the garden. It was 1 ¾ inches long by ⅞ inches wide, compact and lightweight, with a surface layer of gray fur. Before we look inside, let’s review what pellets are and why birds produce them.

Birds form and regurgitate pellets to remove the undigestible parts of their meals. For birds of prey, those elements include bones, teeth, feathers, and fur. Prey is swallowed whole (owls) or with minimal tearing (raptors); then the food is chemically processed in the bird’s first stomach, the proventriculus. Grinding is accomplished not with teeth, but rather with an organ called a “gizzard.” The liquefied, digestible food moves to the bird’s intestines while the insoluble remnants are compressed into the pellet which the bird later coughs up. See The Owl Pages for a clear diagram of an owl’s digestive system. This is a daily ritual, for the bird cannot feed as long as the pellet is blocking its digestive tract.

While hawks and owls are best known for their pellets, other species handle digestion in the same way. Wikipedia’s entry on pellets lists “grebes, herons, cormorants, gulls, terns, kingfishers, crows, jays, dippers, shrikes, swallows, and most shorebirds” as pellet producers. In each case, the bird’s diet is reflected in the contents of its pellets. To get a sense of this variety, see Yorkshire wildlife artist Robert E. Fuller’s website. Among Fuller’s discoveries are goat bones in an eagle pellet, fish scales in a kingfisher pellet, and beetle wings in the pellets of little owls. While you are there, don’t miss his extraordinary images of birds in the process of spitting out pellets. You should also look at the series of red-tailed hawk photos included in “Casting a Pellet” from Outside My Window. At the risk of anthropomorphizing, I must say the experience doesn’t look pleasant!

Kingfisher Pellet (Note all the fish scales.)

Andy Mabbett, CC BY-SA 4.0

One reason that owl pellets receive the lion’s share of attention is that the skeletons found therein are more likely to remain intact. The reason for this, according to The Owl Pages, is that an “owl's digestive juices are less acidic than in other birds of prey.” It’s time to look more closely at our pellet.

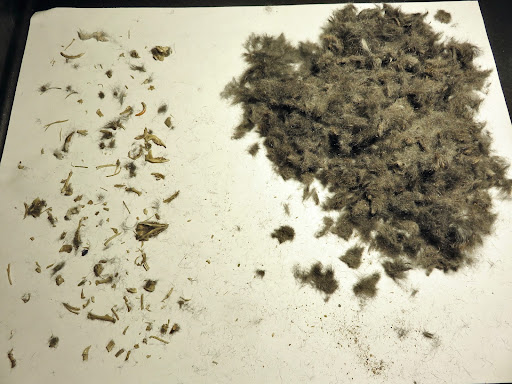

Here are the before and after dissection shots.

April 21, 2022, Easton, MA

Note: The yellow tint of the dissection photos is the result of lamplight. The fur in the pellet was mostly gray with some brown tips and a few white tufts.

Before dissection, a couple of small bones protruded through the fur. I thought I would find more right away, but that was not the case. I gently pried off layer after layer of fur only to reveal some minute tidbits of vegetation and bone fragments. The pile of fur grew as you can see by the space it occupies on this 8 ½ x 11-inch sheet of printing paper. Eventually, larger bones emerged including the following:

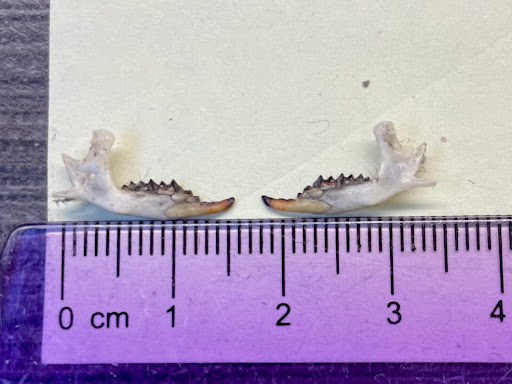

Mandibles (Jaws)

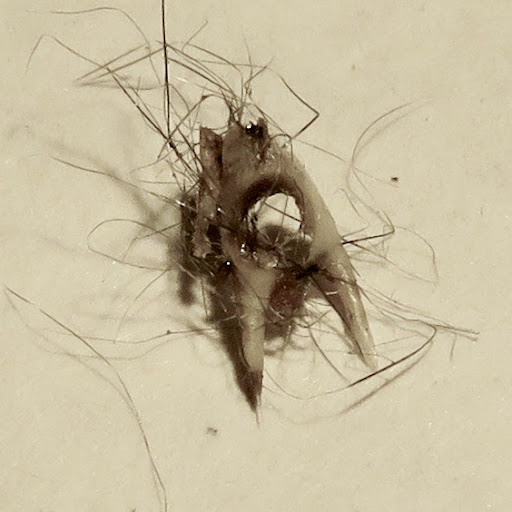

Vertebra

Incisor

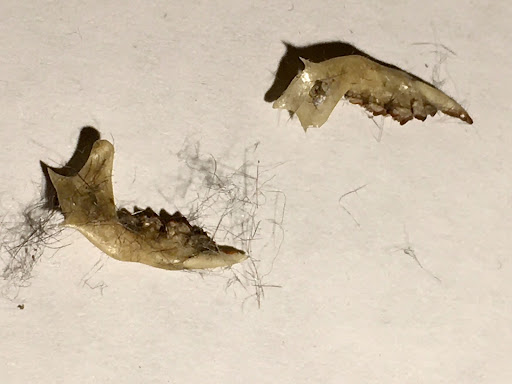

Partial Skull: Lower Jaw, Teeth, Upper Jaw

The pellet also contained ribs, leg bones, and some tiny bone fragments. All of the bones were very small and most were quite fragile. By now, you must be wondering “Which bird produced this pellet?” and “What prey animal did it eat?” Unfortunately, despite my best efforts, I don’t have a definitive answer to either query. What I will share are some observations, experiences, and hypotheses.

Considering the size of the bones and the lack of feathers, the prey was likely a small rodent or a shrew. Pellet bone charts provide a useful starting point in the identification process by simplifying the major anatomical features of common prey animals. Once you have consulted one of these charts, gather more information from experienced naturalists, either in person or through their writings. Discover Wildlife offers some helpful identification tips despite its emphasis on British species. For example, “Shrews have continuous rows of small, pointed teeth, whereas rodents have a gap between the front incisors and the cheek teeth.” The mandibles in our pellet have pointed teeth that stretch the full length of the jaw. As is typical of shrews, the incisors jut forward rather than curving. There is even a bit of red enamel left on the teeth, a diagnostic feature of shrew teeth that reflects their iron content.

Easton Pellet

Easton Pellet

(cropped for emphasis)

© Summit Metro Parks, some rights reserved

(CC-BY-NC)

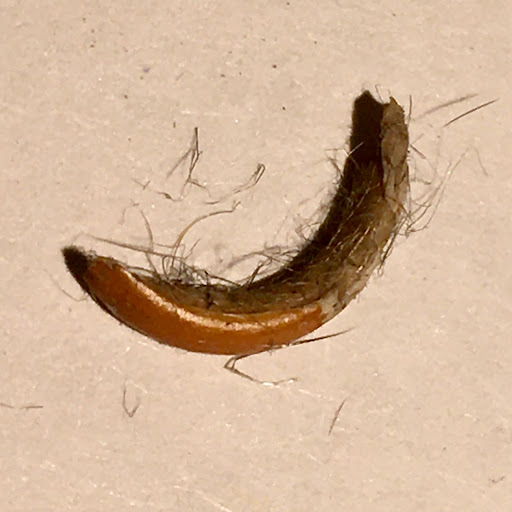

On the other hand . . . the two curved, orange incisors that I extracted point towards a rodent owner: a mouse or meadow vole. Now, look at the zigzag pattern of the teeth in this jaw fragment.

Teeth from Easton Pellet

Copyright Phil Myers, Museum of Zoology, the University of Michigan

Discover Wildlife contrasts the two rodents this way: “The cheek teeth of voles have zig-zag chewing surfaces, whereas rats and mice have three distinct rounded cheek teeth.” At least a portion of our pellet contains meadow vole bones. This implies that more than one prey animal contributed to the pellet I found.

Regarding the pellet maker . . . while not enormous, our pellet was large enough to reflect a large species. Great horned owls have been seen and heard at the library. Red-tailed hawks have been even more conspicuous as they raise their young nearby. Although the pellet didn’t contain a complete backbone and skull(s), it did include a good number of bones. My first impression, like that of my readers, was “owl pellet.”

Sometimes identification is not as clear-cut as we’d hope. Perhaps we lack some detail, some field observation, that would solve the puzzle. Indeed, variation among pellets led a team of Nova Scotian researchers to study DNA from the bird’s digestive system as a means of tracking “ownership.” Read more about their laboratory research at “Who Puked? Raptor Pellets and eDNA”.

If you’d like to find pellets, consider places where a bird might perch or roost while digesting its food. Last week when I walked a trail through the Hockomock Swamp, I scouted beneath some transmission towers, for they seemed like plausible perches. Much to my surprise, I was rewarded with another gray fur pellet and an object that contained a motley assortment of debris. I thought about hawks and owls and the turkey vultures who surely must visit the deer carcasses that hunters leave behind. Mammals leave their sign as well . . . but let’s save that for another week.

I may never excel at pellet ID, but each experience yields greater understanding.

As always, if you know more about this subject, send an email to share your expertise. In the meantime, I will do my part to encourage curiosity and engagement with our world.

Another Pellet! Hockomock, February 12, 2022